Bangladesh Governor's Newsletter August 2018

-

In this Issue:

- Governors Message

- ACP Internal Medicine Meeting, New Orleans 2018

- Educational Program for students

- First CME under new Governor

- First meeting of new committee

- New Fellows in last six months

- New Members in last six months

- Role of Guidelines in clinical practice

- Conclusion

H.A.M. Nazmul Ahasan, MBBS, FCPS, FRCP (Edin and Glasg), MACP, ACP Governor

Governors Message

Happy summer!!

I am privileged to welcome you to ACP-Bangladesh Chapter Newsletter. It's an honor as new Governor to serve the ACP- Bangladesh chapter. After getting recognition, ACP- Bangladesh chapter reached a new height as it received the Chapter Excellence Award in 2017. Establishing a new organization was not an easy task. More than three hundred members added to ACP –Bangladesh chapter just within two and a half years. My heart felt congratulations to Quazi Tarikul Islam FACP, Ex-Governor, ACP-Bangladesh Chapter, and his team who worked hard to establish ACP in the heart and mind of the internists. ACP- Bangladesh Chapter receives all kinds of help from Bangladesh Society, of Medicine, largest platform of Internists.

I hope the process which started before my tenure will continue. We are planning some easy process for our members to pay dues so that their membership will not be dropped. Annual and International conference of Bangladesh Society of Medicine regularly being arranged in December. This year's conference will be held from 7-9 December 2018. As before, ACP-Bangladesh chapter will have a booth at the conference venue. Besides new membership payment, old members and Fellows can pay their dues also. We are communicating with ACP headquarter so that we can help dropped members. All Members and Fellows are requested to pay their annual fees regularly to keep their membership updated. We encourage all members of ACP-Bangladesh Chapter to keep communication with hotline number if they have any query. We are planning that Governors newsletter will have a printed version besides soft copy. Hopefully, we will send you printed version within timeframe. Your feedback will be highly appreciated.

ACP Internal Medicine Meeting, New Orleans 2018

From Bangladesh around a forty-member team joined the ACP meeting in New Orleans.

Governor Elect; Class 2022

HAM Nazmul Ahasan and George M.Abraham

HAM Nazmul Ahasan, new Governor of Bangladesh joined international chapter meeting and talked on following issues.

- Requested for regular presence of ACP ambassador in the annual international congress of Bangladesh society of Medicine that has a dedicated session for ACP Bangladesh chapter.

- Emphasized on collaboration among other regional chapters.

- Due to US VISA issue many of our Members and New Fellows can't enroll in ACP Convocation and Conference. Requested ACP headquarter assist with the issue.

Quazi Tarikul Islam attended the end of Class 2018 and certificate giving ceremony. He also joined International chapter meeting along with Governor elect and addressed following issues.

- Inclusion of diseases in MKSAP from International chapters.

- Invitation of the chapters to select faculty for delivering talk in Internal Medicine meeting of ACP.

- Presentation of the annual report of the chapter.

New fellows in Convocation ceremony.

Quazi Tarikul Islam as Poster judge

Prof. Hans Peter Kohler with dignitaries from Bangladesh

MA Jalil Chowdhury, Quazi Tarikul Islam & HAM Nazmul Ahasan.

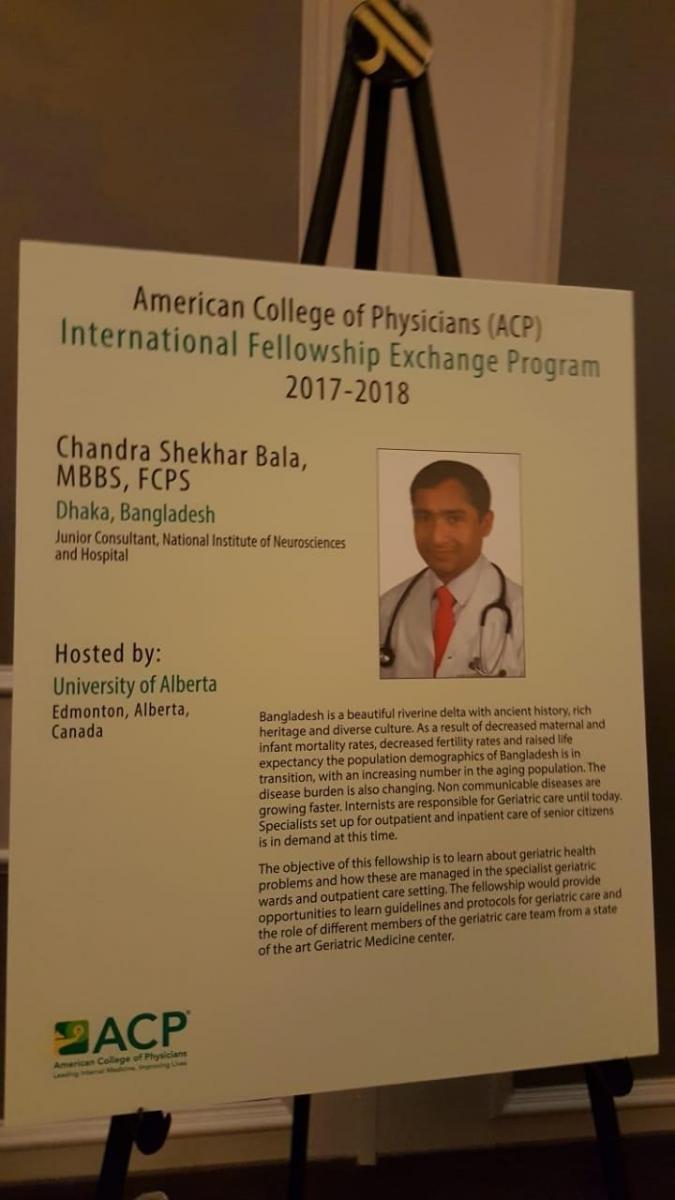

Chandra Shekhar Bala, FACP awarded ACP International fellowship exchange program 2017-2018. Hosted by University of Alberta, Canada.

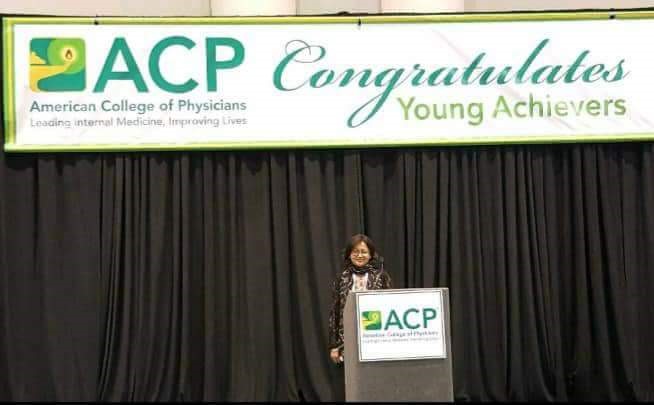

Dr. Madhabi Karmaker, resident member of Bangladesh chapter won the poster competition in BSM Conference in Dhaka during 2017. As a chapter winner, she attended ACP conference in New Orleans 2018.

Chandra Shekhar Bala, FACP

Madhabi Karmaker

Chapter Excellence Award

Bangladesh Chapter Receives 2017 Chapter Excellence Award. The award recognizes chapters which successfully meet the standards for managing a chapter. In order to achieve the Chapter Excellence Award, chapters must meet all basic criteria and ten optional criteria.

Educational Program for students

An educational program for student's member of ACP- Bangladesh chapter held on 3 rd March 2018. Dr. Motlabur Rahman, Associate Professor of Medicine spoke on “doctors patient relationship”. Prof. Md. Faizul Islam Chowdhury, Chair, Medical Students committee was also present on the occasion. Nearly sixty students attended the meeting.

Dr. Motlabur Rahman

Quazi Tarikul Islam, Md. Faizul Islam Chowdhury & Md. Titu Miah

First CME under new Governor

ACP bangladesh Chapter arranged 1 st CME under new Governor HAM Nazmul Ahasan in the premises of Dhaka Club on 8 th July 2018. Prof. Khawaja Nazim uddin FACP spoke on “ Management of Diabetis – An update”. Nearly 150 members of ACP-Bangladesh Chapter were present. Prof. Billal Alam, President, Bangladesh society of Medicine was also attended.

Prof. Khwaj Nazim Uddin

HAM Nazmul Ahasan, Governor ACP-Bangladesh Chapter

Quazi Tarikul Islam and HAM Nazmul Ahasan

Prof.Md.Billal Alam, President Bangladesh Society of Medicine

Attendees at Scientific seminar

First meeting of new committee

Governor, HAM Nazmul Ahasan addressed new members of both advisory council and chapter leaders. First meeting of advisory council was held on 14 th July at Absolute BBQ. Following decisions were taken in the meeting.

- All the attendees praised Prof. Quazi Tarikul Islam, passing Governor, for his excellent work and contribution during his tenure.

- A Scientific calendar for ACP-Bangladesh Chapter to be formulated.

- ACP-Bangladesh chapter will arrange program in coordination with Bangladesh society of Medicine.

- A delegation of members of ACP- Bangladesh chapter will join Conference at Lucknow, India, organized by ACP-India Chapter.

- Prof. AKM Aminul Hoque, FACP will remain as treasurer of ACP-Bangladesh chapter.

- Dr. Mohammad Rafiqul Islam, FACP will act as Secretary to Governor.

Meeting of Advisory council members (ACP-Bangladesh Chapter)

New Fellows in last six months

A.S.M. Areef Ahsan, MBBS, FACP

Umma Salma, FACP

Mohammad Robed Amin, FACP

Mohammad Abdus Sattar Sarker, FACP

Sudip Ranjan, FACP

A K M Humayon Kabir, FACP

MD Motlabur Rahman, FACP

Mohammad Murad Hossain, FACP

Ahmedul Kabir, FACP

Abul Bashar M Nurul Alam, FACP

New Members in last six months

Mohammad Mehfuz-E Khoda, MD

Ishrat Bhuiyan, MBBS

Mahmudul Hasan

Nitai Chandra Ray, MBBS, MD

Mohammed Amdad Ullah Khan, MD

Jahir Uddin Mohammed Sharif, MD

Mohammad Wahidur Rahman, MBBS

Mohammad Kamruzzaman Mazumder, MD

Mohammad Nadim Hasan, MBBS

Md. Ahsanul Kabir, MBBS

Ripon Chandra Majumder, MD

Foysal Ahamed, MBBS

Mohammad Ariful Islam, MBBS

Saiful Patwary, MD

Md. Abdus Sabur Talukder, MBBS

Choudhury Faisal Rahim, MD

Prashanta Kumar Shil, MBBS

Sobroto Kumar Roy, MD

Dulal Chandra Das, MBBS

Amrita Kumar Debnath, MBBS

Mohammad Zaynal Abedin, MBBS

Subrata Kumar Paul, MBBS

Md. Abdulla-Al Maruf, MBBS

Hafizur Rahman, MBBS

Swapan Kumar Singha, MBBS

Md. Aminul Islam, MBBS

Rozana Rouf, MBBS

Md. Saiful Malek, MBBS

Shantonu Kumar Saha, MBBS

Utpal Sarkar, MBBS

Makhan Lal Paul

MD HOSSAIN, MBBS

Tapash Saha, MBBS

Mohammad Motiur Rahman

Md.Abdur Razzaque

Ishrat Binte Reza, MBBS

Arif Atique, MBBS

COL Mohammad Mizanur Rahman, MBBS

Murshed Ahamed Khan

Mizanur Rahman, MD

Abdullah Al Muti

Farhana Sultana, MBBS

Mohammad Shamsuddoha Shanchay, MBBS

Proshanta Kumar Shil

Sultan Ahmed, MBBS MD

Role of Guidelines in clinical practice

Prof. Quazi Tarikul Islam FACP

Over the past decade, clinical guidelines have increasingly become a familiar part of clinical practice. Every day, clinical decisions at the bedside, rules of operation at hospitals and clinics, and health spending by governments and insurers are being influenced by guidelines. The development and implementation of (evidence-based) clinical practice guidelines is one of the promising and effective tools for improving the quality of care. However, many guidelines are not used after dissemination. Implementation activities frequently produce only moderate improvement. The guideline recommendations are followed in on average 67% of the decisions, but there is a large variation between different physicians and between different guidelines. Specific strategies designed to handle possible obstacles to implementation are needed to improve adherence It is important to study specific guideline programs in detail to learn from their successes and failures. 1

A program to implement a guideline should be well designed, well prepared, and preferably pilot tested before use. Such a program should be built into the normal channels and structures for improving care. More research into the details of implementation is needed to better understand the critical determinants of change in practice.

Extensive research has been undertaken over the last 30 years on the methods underpinning clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), including their development, updating, reporting, tailoring for specific purposes, implementation and evaluation. This has resulted in an increasing number of terms, tools and acronyms. Over time, CPGs have shifted from opinion-based to evidence-informed, including increasingly sophisticated methodologies and implementation strategies, and thus keeping abreast of evolution in this field of research can be challenging 2.

Clinical practice guidelines are statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.

Clinical practice is defined as a model of practice that involves those activities with and on behalf of clients, especially those activities completed in the client's presence and with the client's collaboration. These activities are informed by an ecologically based biopsychosocial assessment.

A medical guideline (also called a clinical guideline or clinical practice line) is a document with the aim of guiding decisions and criteria regarding diagnosis, management, and treatment in specific areas of healthcare. ... They usually include summarized consensus statements on best practice in healthcare.

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is a problem-solving approach to the delivery of health care that integrates the best evidence from wel-designed studies and evidence-based theories with a clinician's expertise and a patient's preferences and values in making the best clinical decisions (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2014) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 . Clinical practice guidelines, which should be routinely incorporated into EBP, are statements with recommendations for clinical practice that are rigorously developed based on systematic reviews of evidence and an evaluation of their benefits and harms (Melnyk et al., 2012) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 . Guidelines are important tools in EBP that can reduce healthcare variation and improve patient outcomes. However, guidelines produced from multiple sources often conflict with one another, which can be confusing for clinicians. Further, many clinicians unknowingly follow recommendations and guidelines that have not undergone rigorous development.

Since many clinicians turn to their professional organizations to provide guidelines that can be incorporated into care, it is critical for them to understand not only how guidelines should be formulated, but also how to critically appraise them and where the best “gold standard” guidelines can be accessed.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the United States has described eight attributes of good guideline development (IOM, 2011) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 . These attributes include: (a) validity, (b) reliability and reproducibility, (c) clinical applicability, (d) clinical flexibility, (e) clarity, (f) documentation, (g) development by a multidisciplinary process, and (h) plans for review.

Once a CPG is accessed, critical appraisal of the guideline should be performed. Strength of clinical practice guidelines is based on their validity and reliability of the recommendations (Grinspun, Melnyk, & Fineout-Overholt, 2014) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 . Some key rapid critical appraisal questions to ask when reviewing a CPG include:

- Who were the guideline developers?

- Did the team have a valid development strategy?

- Was an explicit, sensible and impartial process used to identify, select, and combine evidence?

- Did the developers carry out a comprehensive, reproducible literature review within the past 12 months of its publication or revision?

- Were all important options and outcomes considered?

- Is each recommendation in the guideline tagged by the level or strength of evidence upon which it is based and linked with the scientific evidence?

- Has the guideline been subjected to peer review and testing?

- Are the recommendations clinically relevant?

Will the recommendations help me in caring for my patients (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt,2014) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 ?

It must be remembered that access to and dissemination of CPGs alone often does not result in their wide-scale uptake in real world practice settings. Implementing CPGs in healthcare systems often requires a multipronged approach that includes targeted intervention strategies with both clinicians and the healthcare system (Grinspun, Melnyk, & Fineout-Overholt, 2014) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 . The culture and environment of the system in which the CPGs are to be implemented must be carefully assessed in order to identify strengths and barriers to adoption of the new guideline, followed by the development of a strategic plan to overcome barriers in widespread implementation. Top leadership and middle management support, provision of EBP mentors, grassroots efforts by clinicians, along with tools and resources that support implementation are all necessary for successful wide-scale adoption and sustainability (Melnyk, 2007, https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 2014) https://sigmapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/wvn.12079 .

Clinical guidelines that is stretching across Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, and Africa has its origin in issues that most healthcare systems face: rising healthcare costs, fueled by increased demand for care, more expensive technologies, and an ageing population; variations in service delivery among providers, hospitals, and geographical regions and the presumption that at least some of this variation stems from inappropriate care, either overuse or underuse of services; and the intrinsic desire of healthcare professionals to offer, and of patients to receive, the best care possible. Clinicians, policy makers, and payers see guidelines as a tool for making care more consistent and efficient and for closing the gap between what clinicians do and what scientific evidence supports.

As guidelines diffuse into medicine, there are important lessons to learn from the firsthand experience of those who develop, evaluate, and use them.3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1114973/ This article, the first of a four part series to reflect on these lessons, examines the potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. Future articles will review lessons learned about their development,4 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1114973/ legal and emotional ramifications,5 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1114973/ and finally their implementation.6 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1114973/

Summary points

- Clinical guidelines are an increasingly familiar part of clinical practice

- They have potential benefits and harms

- Rigorously developed evidence based guidelines minimize the potential harms

- Clinical guidelines are only one option for improving the quality of care.

Potential benefits for patients

For patients (and almost everyone else in health care), the greatest benefit that could be achieved by guidelines is to improve health outcomes. Guidelines that promote interventions of proved benefit and discourage ineffective ones have the potential to reduce morbidity and mortality and improve quality of life, at least for some conditions. Guidelines can also improve the consistency of care; studies around the world show that the frequency with which procedures are performed varies dramatically among doctors, specialties, and geographical regions, even after case mix is controlled for Patients with identical clinical problems receive different care depending on their clinician, hospital, or location. Guidelines offer a remedy, making it more likely that patients will be cared for in the same manner regardless of where or by whom they are treated 7.

Potential benefits for healthcare professionals

Clinical guidelines can improve the quality of clinical decisions. They offer explicit recommendations for clinicians who are uncertain about how to proceed, overturn the beliefs of doctors accustomed to outdated practices, improve the consistency of care, and provide authoritative recommendations that reassure practitioners about the appropriateness of their treatment policies. Guidelines based on a critical appraisal of scientific evidence (evidence based guidelines) clarify which interventions are of proved benefit and document the quality of the supporting data. They alert clinicians to interventions unsupported by good science, reinforce the importance and methods of critical appraisal, and call attention to ineffective, dangerous, and wasteful practices.

Potential harms to healthcare professionals

Flawed clinical guidelines harm practitioners by providing inaccurate scientific information and clinical advice, thereby compromising the quality of care. They may encourage ineffective, harmful, or wasteful interventions. Even when guidelines are correct, clinicians often find them inconvenient and time consuming to use. Conflicting guidelines from different professional bodies can also confuse and frustrate practitioners.9 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1114973/ Outdated recommendations may perpetuate outmoded practices and technologies.

In Bangladesh we have many guidelines for treating many diseases. Most of the guidelines have developed for the treatment of Infectious diseases. All the guidelines are prepared in the light of WHO and other international standard guideline from Europe and USA. We have success and failure both. In treating and controlling Malaria, Visceral Leishmaniasis, Influenza A H1N1pdm09, Dengue Fever we have achieved remarkable success. On the other hand, we have failure in controlling other Arboviral infections and non-communicable diseases. But unfortunately evidenced based guideline had not been published ever. We are not doing rigorous exercise for the data, clinical experiences, and the management skill which may be different from other countries of the world as described in their guideline. Ethnicity and race plays an important role discriminating treatment response among them. Drug dose of a Caucasian must vary from an Asian.

Our target to achieve standard clinical guideline is completely depending upon evidenced based data.

References

- Grol, Richard. Successes and Failures in the Implementation of Evidence-Based Guidelines for Clinical Practice, Medical Care: August 2001 - Volume 39 - Issue 8 - p II-46-II-54. Tamara Kredo, Susanne Bernhardsson, Shingai Machingaidze, Taryn Young, LouwOchodo Karen Grimmer. Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play, International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 28, Issue 1, 1 February 2016, Pages 122–128

- Field MJ, Lohr KN, editors. Guidelines for clinical practice: from development to use. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1992.

- Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Developing guidelines. BMJ (in press).

- Hurwitz B, Eccles M. Legal, political and emotional considerations of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ (in press).

- Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, Griffiths C, Grimshaw J. Using clinical guidelines. BMJ (in press).

- Chassin MR, Brook RH, Park RE, Keesey J, Fink A, Kosecoff J, et al. Variations in the use of medical and surgical services by the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 1986; 314:285–290. [PubMed] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3510394

- Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Using clinical practice guidelines to evaluate quality of care. 1. Issues. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services; 1995. (AHCPR publication No 95-0045.)

- Feder G. Management of mild hypertension: which guidelines to follow? BMJ. 1994; 308:470–471.

Professor Quazi Tarikul Islam

Prof. of Medicine

Email: Prof.tarik@gmail.com

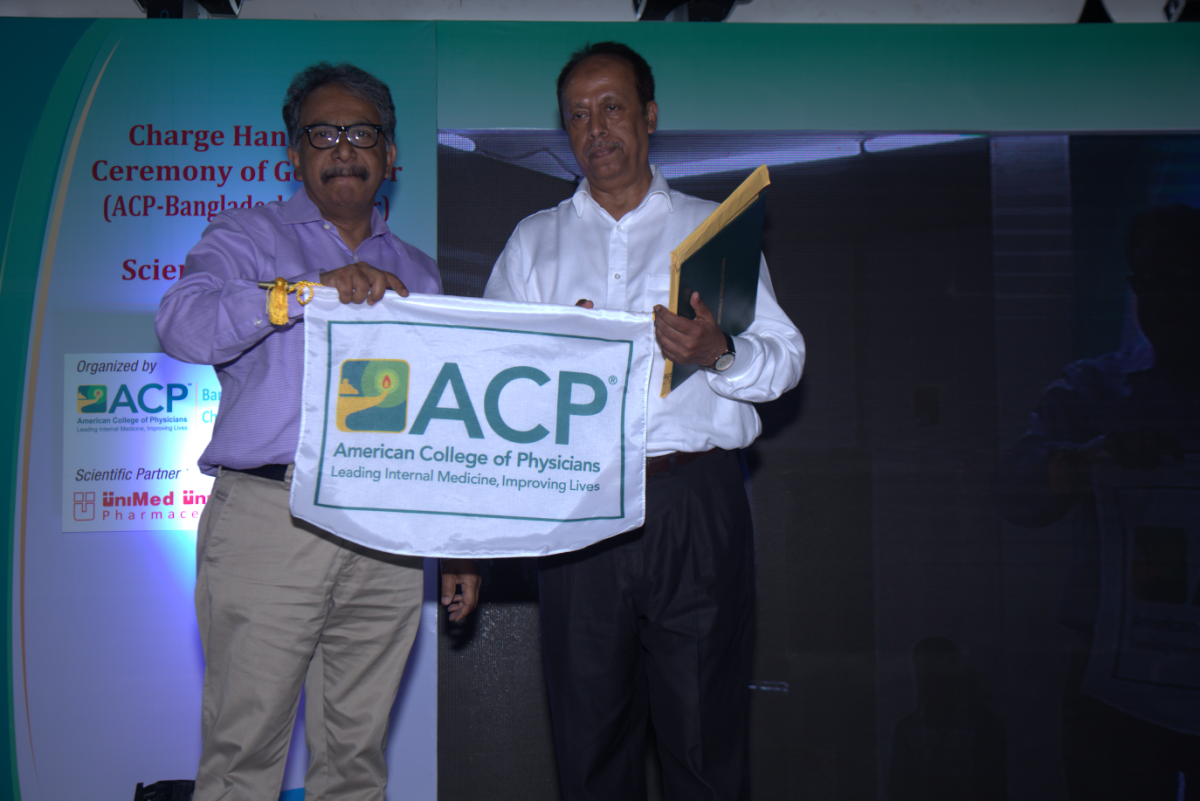

Conclusion

This is first newsletter of my tenure. Prof. Quazi Tarikul Islam handed over the baton of Governorship to me. He is the founding Governor of ACP-Bangladesh Chapter. His contribution in the development and enrichment of the chapter is immense. Bangladesh Society of Medicine (BSM) is our parent society. We always love to work with the BSM. We are stepping forward to work closely with regional ACP chapter like India Chapter, Saudi Arabia Chapter, Japan Chapter and ASEAN Chapter. We are looking forward to organize more CME this year and skill development program for Residents/Fellow and student members.