James S. Withers, MD, FACP

Medical director and founder, Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net; founder, Street Medicine Institute; teaching faculty, UPMC Mercy; assistant professor, clinical medicine, University of Pittsburgh

— MEDICAL SCHOOL —

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

— RESIDENCY —

The Mercy Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

With a childhood filled with tagging along on house calls with his father, a family practice physician in rural Pennsylvania, and helping his mother, a nurse, deliver Meals on Wheels (and learning how to parallel park), Dr. Jim Withers would seem to have been destined to become a physician.

“I had the best examples,” Dr. Withers says of his parents. “They were great. Even greater, in our teen years in the early 1970s, they took the whole family to work medically in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Saint Lucia. It just seemed like a normal childhood, but looking back on it, it was really special.”

He entered the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine with idealism and a “sense of the sacred nature of the field and what a blessing it was to be with people,” he says. However, the luster eventually wore off because he realized there were a lot of people there who seemed to be not quite like his parents.

... you don't learn as much unless you have to immerse yourself in someone else's reality.

“It was like a bunch of people got lost there, and they weren't sure how they got there. Some of the people were bitter about the workload. The spirit was often not there. The sacredness of the service to people, they just didn't seem to have direct access to that. To me, that was a missing part of the curriculum,” Dr. Withers recalls.

When he began teaching, he decided to include humanism in the curriculum. “We had to have the right conditions and the right openness to let students take the white coat off, existentially, and be a person first and then be present to people with things like house calls and touching people.”

Dr. Withers' first thought was to go back to the jungle. The hospital approved the trip, but he had to use four weeks of vacation. He went to work in Belize and found the experience to be exhilarating. “But I got back and thought, ‘wow I don't have any more vacation this year and nothing has changed in Pittsburgh.’”

He wanted to create a program that would work with people who were excluded from getting proper care and create a classroom of the streets, and he wanted to find the “orneriest, most uncooperative” patients he could possibly find. “Because, I thought, you don't learn as much unless you have to immerse yourself in someone else's reality.”

Dr. Withers began to think about the homeless living under bridges in Pittsburgh, which in his mind, might as well be the jungle. He sought out a formerly homeless man who was distributing blankets to people living on the streets and asked if he could take him to meet and treat others in need of medical care. “I had to talk him into it, and he told me not to dress like a doctor,” he recalls.

We had to have the right conditions and the right openness to let students take the white coat off, existentially, and be a person first and then be present to people with things like house calls and touching people.

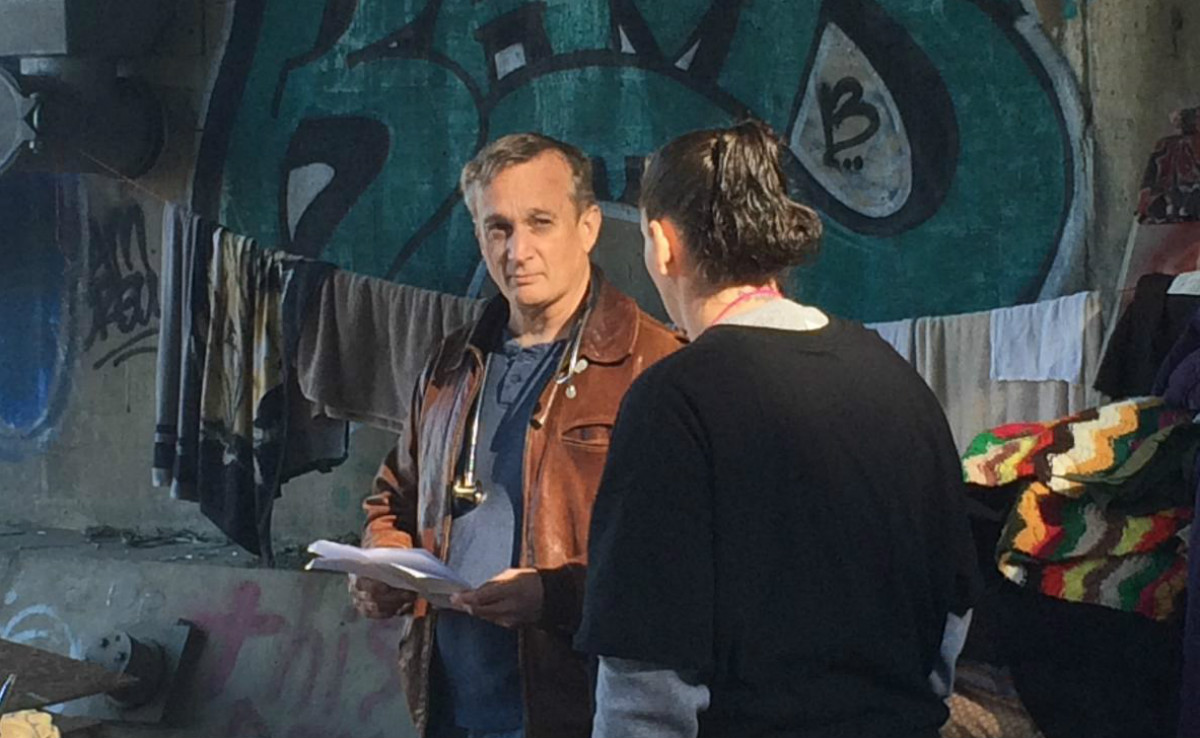

“I began to sneak out at night to work with him. It was another world. It was almost too much of another world to grapple with. However, I knew once I made the steps out there that I couldn't turn back because then I saw stuff that I couldn't forget. People became very real to me, and so for a while I was teaching by day and sneaking under bridges, dressed like a homeless person at night,” Dr. Withers says.

Just as he wanted, the patients were difficult. “They were not about to go for health care because they did not like us at all. I then began to hear their voices and understand how it looked from the street, and it was everything I wanted from a classroom. So I was the first student and then very quickly other students came along,” he says. And Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net was born.

Dr. Withers eventually told hospital administrators what he was doing, they enthusiastically supported him and the creation of Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net, a medical and social service outreach program for persons who are experiencing homelessness. After receiving start-up funding through a Pittsburgh Mercy Care for the Poor Fund grant, Operation Safety Net became an official Pittsburgh Mercy outreach program in 1993, and Dr. Withers continues to serve as the program's full-time medical director.

In 2008, Pittsburgh Mercy, a member of Trinity Health, serving in the tradition of the Sisters of Mercy, helped Dr. Withers create the Street Medicine Institute, a separate 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Following the same innovative care model created by Dr. Withers and Operation Safety Net in Pittsburgh, today there are more than 200 street medicine programs around the world like it on six continents, and 35 medical schools now have street medicine programs. “And that's mostly due to our former students creating them,” he says.

ACP, Dr. Withers says, has given him the opportunity to further his medical knowledge and network. He admires ACP's advocacy efforts on behalf of internal medicine and “the human needs of our art.” ACP's commitment to education is well known, he says, which is important as he teaches and trains the next generation of internists.

Being an internist affiliated with a mission-driven, community health and wellness organization like Pittsburgh Mercy has allowed him to do his work on the streets without interruption for more than 26 years. “The way you can craft your career is greater in internal medicine than maybe any specialty, but you can also use internal medicine to connect to your passion for humanism and social justice. Social justice is important to the students I work with. It's just been undernourished by their teaching careers. Some of them almost cry when they leave the rotation and they say thank you. About a year ago, one student told me she got her common sense back, which I thought was great feedback.”

Life isn't all about medicine for Dr. Withers. He loves spending time with his four grandchildren and is anxiously awaiting the arrival of a fifth. He's also done some mountaineering (and taught it as well) and belongs to a club in Pittsburgh. He's scaled Mexico's Pico de Orizaba, the third-highest peak in North America at nearly 19,000 feet.

Dr. Withers has received much recognition for the Street Medicine Institute, including being named one of CNN's Top 10 Heroes of 2015. “The awards are meaningful professionally, but they're also a little out of my comfort zone,” he admits. The CNN award “was exciting, and it seemed to generate a lot more attention than I would've thought. So that's good because people then became interested in the work and then they began to care about the people. So that was all good.”

His work to help the most vulnerable has taken him from the inner city to remote villages around the world. Years ago, he saw a sign in a hospital in Haiti with a quote from Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu that simply reads, “Go to the people.” That phrase became the tagline for the Street Medicine Institute. And it's the way Dr. Jim Withers lives his life.

Photos copyright Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net. Used with permission.

For more information about the innovative work of Pittsburgh Mercy's Operation Safety Net, visit www.pittsburghmercy.org.

For more information about the work of the Street Medicine Institute, visit https://www.streetmedicine.org/.

Back to the August 2019 issue of ACP IMpact

More I.M. Internal Medicine Profiles